by Max Schröder

The neoclassical study of income distribution depends heavily on the notion of Marginal Productivity Theory (MPT). Apart from the (often admitted) practical (read measurement) problems with this account, the MPT also lacks a rigorous philosophical underpinning. The unwillingness to part with the account despite its evident theoretical and practical shortcomings is one of the many failures that can be witnessed in mainstream economics today.

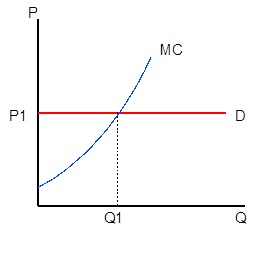

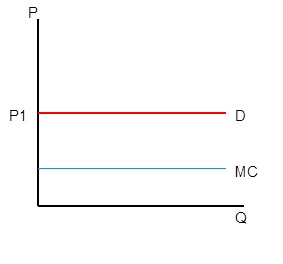

The fundamental question of (in)equality is: “What is a fair or just distribution?” The answer to this question – drawing on some Calvinist-Protestant ethic – which can be found in most developed economies today is this: “A fair distribution is one where everyone receives a part of the general income that is (more or less) proportional to the contribution one has made to the general income.” And free markets (in theory) do just that. According to neoclassical economic theory free markets distribute income according to the marginal productivity principle – everyone labourer and capital(ist) is payed the exact contribution they have made to aggregate production.

The MP account has long been used to justify discrepancies in pay, but in the light of exploding executive salaries the MPT has been increasingly challenged. In the following I hope to show that MPT lacks a solid philosophical basis and is thus unable to perform its desired function. We will thus see that the distribution of income is far less “naturally determined” and therefore should be under more scrutiny from society.

The notion of MP is in essence a causal claim: Your marginal productivity is whatever change in the output that is caused by your actions. The problem that arises now is that causation as a philosophical concept is far less straightforward than is commonly understood. Even though philosophers are not agreed on the correct account of causation they understand that causation mostly works from multiple causes to effect rather than from a single cause. Failure to properly account for all the relevant causes might lead one to overestimate the impact that a single variable might have in bringing about a large effect. This is not to say that small causes cannot have impressive effects. A spark might still cause a forest fire, but only if there is dry scrub around, if it is not raining, and the if there is oxygen present, and so forth. In short a cause can only be effective in bringing about an effect if the right background conditions are prevailing. (In the lingo: The cause and the background conditions form a sequence of jointly sufficient conditions).

The main problem for MPT is that it discounts for these background conditions and proceeds from a situation where everything but one cause is fixed: ceteris paribus. To see the flaws of this system one only has to consider a simple example: Imagine that there are two workers, A & B, who operate a machine that produces 100 units of output. Now, given that the machine only works when operated by 2 people we can now show that B’s marginal productivity is 0 or 100 depending which background conditions we choose. If we assume that A is not operating the machine B’s MP will be 0 – which is the change in output from when no one is operating the machine (0) to after B has started working (also 0). Now let’s assume that A is already operating the machine. In this case B’s MP will be 100, since that is the change from the output given that only A is working (0) to the output produced after B joins in as well (100). Clearly a focus on singular causes leaves us with a distorted (and wrong) estimation of the impact of B’s work. Please note that I have abstracted from the MP of the machine to illustrate my point – obviously this would complicate matters more.

In complex situations (such as production in a modern economy) the presence and exact position of the background conditions are important to evaluate the impact of a single cause. This can be seen by modifying the above example a little. Now assume that A is already working and the machine produces 30 units of output. After B joins output is up to 100 units. This seems to be a more straightforward (since less ridiculous) example – from a MPT perspective A’s MP is 30 and B’s 70. Again this is not enough since it might be the case that B´s productivity has been amended by A’s work. In order to distinguish between the productivity due to B’s work effort and the productivity due to the position of his or her work in the web of jointly sufficient conditions, we would have to swap A & B and compare the resulting outcome against the one observed. If it turns out that in the reverse example A’s MP is 70 and B’s productivity is 30 we would have evidence that the higher productivity of B is not so much due to his or her work effort and skill as to the particular position he or she occupies in the production process.

The results of these thought experiments bring bad news for MPT. Neither is it possible to evaluate the impact of a single worker whilst discounting for background conditions, nor is it possible to attribute an individual’s MP entirely to their work effort and skill.

The lessons we can draw, however, are powerful. First: background conditions matter. The success of some individuals and companies is largely enabled by the web of institutions (rule of law, public infrastructure, public education, work ethic, etc.) around them. Some of these – but by no means all – can reasonably be taken for granted (read held fixed): the existence of oxygen on earth might be necessary for the success of Microsoft, but I see no need to attribute any role to the big bang. Others have to be acknowledged (such as the existence of a school system that provides for an educated workforce) and deserve to be compensated for the role they play in the production process (e.g. trough taxes that help fund a public school system).

Second: The case of background conditions shows us that the relative position of a job within the production process might matter more than the individual who occupies it. This cuts through the traditional view that productivity is a sign of personal exertion and ability – some jobs just are naturally more productive than others simply due to the position they occupy in the web of jointly sufficient causes. The existence of these differently weighted positions requires a nuanced view of what a worker’s “real” contribution amounts to. Failure to do so might leave us with a gross overestimation of what certain individuals contribute to the general wellbeing.

The way ahead is long and riddled with complications. The excesses of income inequality witnessed in developed economies for the last 30 years have caused a lot of disturbance and are rightfully subject to increased criticism from politics, society and academia. Luckily MPT becomes increasingly untenable as a way to justify these discrepancies. With the breakdown of MPT we can see that reward in society is as much a matter of convention, social status and power as it is of productivity and it is important that we take account of these facts if we are interested to attain anything like a fair distribution of income. It is not enough to let the markets deal out their spoils. Society has to scrutinise market outcomes and reign in their worst excesses.

What is important now is to devise a nuanced account of just distribution that acknowledges the organic structure of society and takes account of background conditions whilst allowing room for reward of individual effort and skill. This task is cut out not for an individual, but can only be attempted by society as a whole – trough honest conversation to arrive at solution that is beneficial to all. The task is hard, but in all likelihood worth the effort.